A few years ago, we, the descendants of Hans Wittwer, were invited by the gta, the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture, to reassess the question of the copyright of our ancestor's work. Bruno Maurer, the director of the institute, took the opportunity to show us Hans Wittwer's estate stored at the gta. While we listened to the director of the institute and his staff, my father, Kaspar Wittwer, studied the plans of the restaurant that his father had designed and built for Halle-Leipzig airport. Kaspar Wittwer was the first of Hans Wittwer's three sons to be born in Halle in 1930 and he was not quite four years old when the young family returned to Basel. Hans Wittwer had lost his job as a teacher at the Halle School of Arts and Crafts at Burg Giebichenstein and there was strong opposition to the continuation of his plans for the Halle-Leipzig airport.

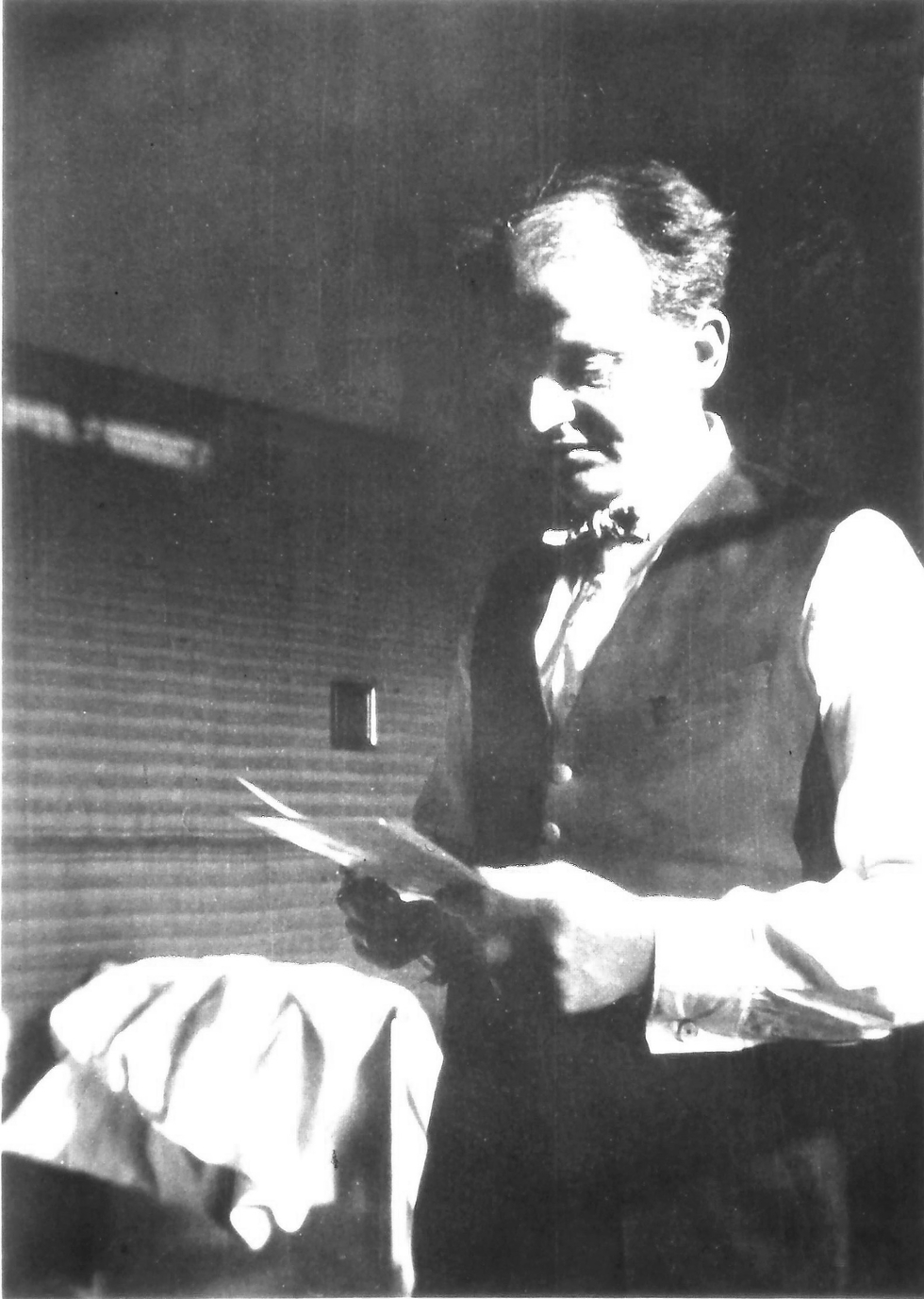

When we took the train back from Zurich to Basel after visiting the gta, my father told me that his father sometimes explained to him the plans he had drawn in Halle for the airport restaurant. On Sundays, he recalled, they climbed the stairs to the attic, where Hans Wittwer had set up a kind of office. There was a tall cupboard containing all kinds of documents from earlier years, including the plans for the airport restaurant in Halle. This cupboard was now opened and the plans inside were pulled out and laid out. His father explained to him what a plan was and what it was for, what the lines on the paper meant and, finally, how he had arrived at the architectural solutions he had come up with. "Look," his father kept telling him, "I did it this way and that way for this reason". This joint viewing of old designs and plans gradually became less frequent and eventually stopped altogether. It probably came to an end after 1945, when Hans Wittwer learned that the airport restaurant had been destroyed in the war. It must have been a terrible blow for the now fifty-year-old that the building, which he had once described as his calling card and with which he had wanted to establish his career as an independent architect, lay in ruins. Reconstruction was probably never even up for discussion. In terms of timing, this fits in well with the memories of Hans-Jakob Wittwer (1935–20217), the youngest son of Hans and Jula Wittwer-Rieder, who, according to his own testimony, had not heard anything about looking at old plans and documents together and was therefore under the impression that they, Hans Wittwer's three sons, knew nothing at all about their father's professional past. However, it also took a visit to the gta to reawaken my father's memories of the hours in which his father explained his thoughts and decisions when designing his buildings.

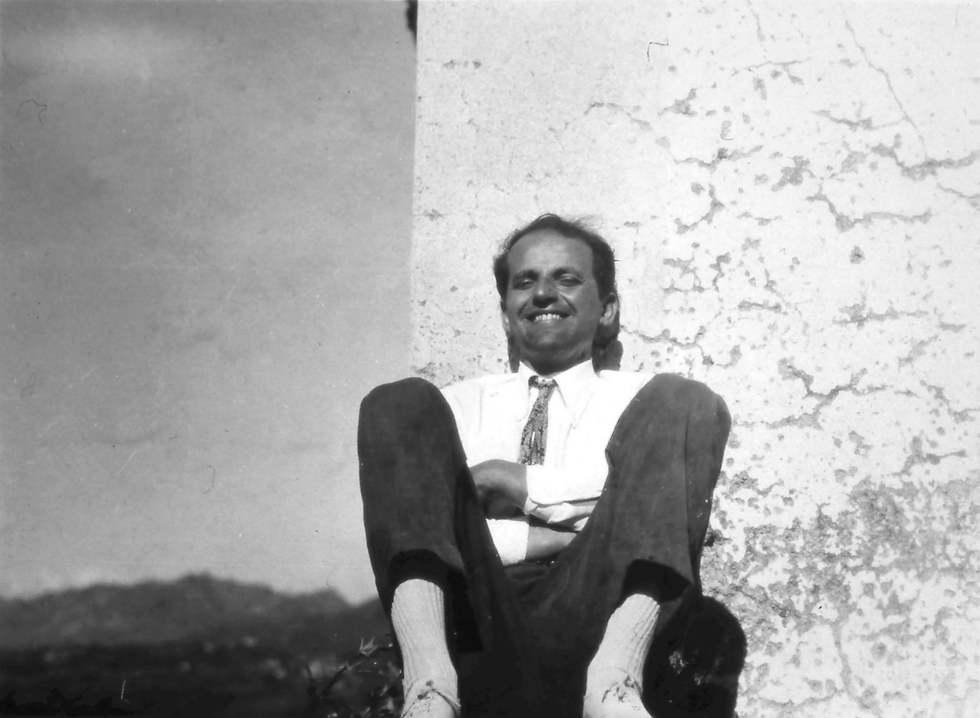

In the family circle, Hans Wittwer was called either "Bappeli" (= little father) or "Gletzli". The word "Gletzli" can have two meanings. Firstly, it means "little bald head", apparently Hans Wittwer had a tendency to go bald at an early age. However, as in Basel dialect the "K" before a consonant is soft, i.e. pronounced like a "G", "Gletzli" can also mean a small block, probably alluding to the architecture he preferred and actively promoted, in which conventional roofs covered with tiles or shingles were not used.

Even when Hans Wittwer was no longer working as an architect himself, his interest in architecture remained alive. When he was out and about with his sons, he would always point out individual architectural details to them. In his eyes, an important criterion for judging architecture was the lighting. For example, he was annoyed by canopies that cast shadows on the doors or windows below. What interested him most about new buildings was whether and how they fitted in with their historical surroundings. For example, he criticized new buildings that bordered older buildings on both sides for not taking into account the floor height and façade division of the buildings to their left and right in their façade structure. He was annoyed by the fact that a public building constructed in the early 1940s towered unattractively over the row of medieval or baroque houses in front of it.

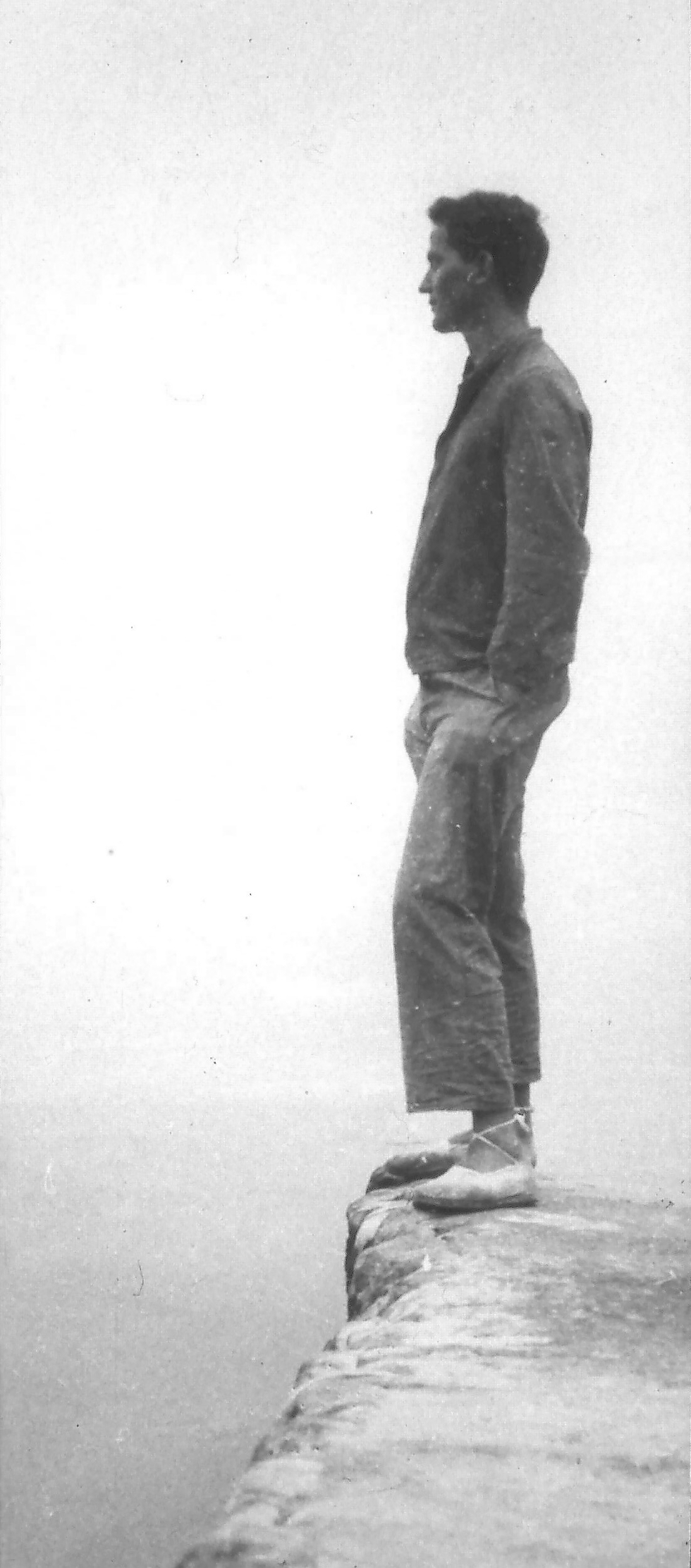

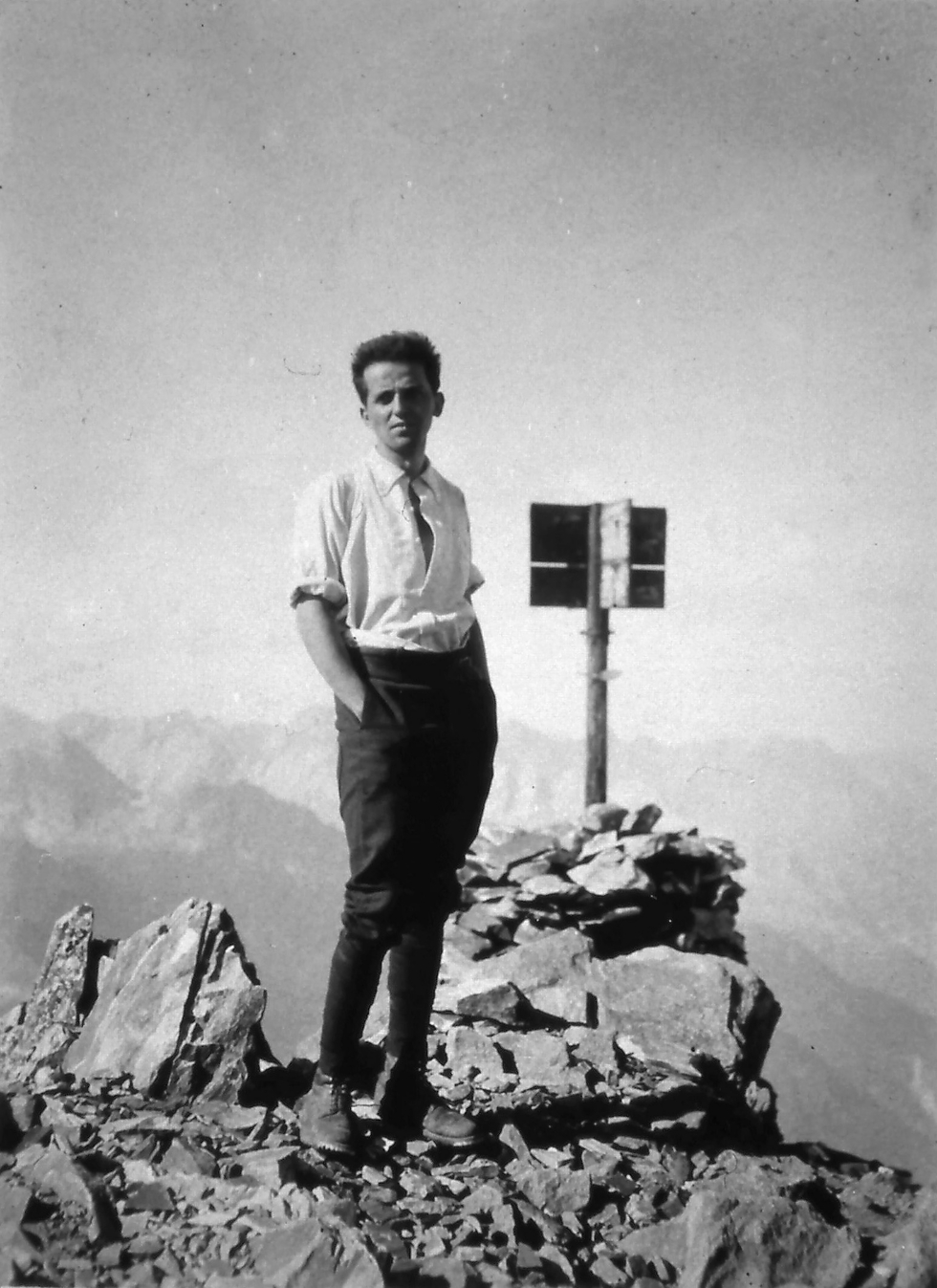

There wasn't much talk about my grandfather in the family and yet somehow he always seemed to be a bit present. Perhaps because my grandmother, who outlived him by more than five decades, had numerous reminders of him within her four walls. Works of art, like the furniture and everyday objects from his time at the Bauhaus or at the castle - many by artists who were friends of his and his wife's - and the odd watercolor that Hans Wittwer had painted on his travels in England and Scotland, in the countryside around Halle that he loved so much, or in Switzerland. From my father's stories, I also learned that his father had an almost boundless good nature and indulgence. Even when things got loud in the household with the three growing boys and their exuberance was about to turn into wantonness, he remained completely calmly focused on his respective occupation in the midst of the commotion and seemed oblivious to the noise around him. It then took a word of warning from his wife for him to put his foot down and bring his three sons to their senses. Nevertheless, he must have been determined in his own way, his ideas were respected and his plans carried out, even if they demanded a lot from the family. This was very evident during their vacations and outings. At a young age, Hans Wittwer shared the general enthusiasm of his generation for the mountains and the emerging winter sports. As his three sons grew up, this interest in the mountains remained alive, but now many trips were also made to the Swiss Jura, which was easier and quicker to reach from Basel. Hans Wittwer was particularly fond of the area around Lake Biel. The isolation of Switzerland during the Second World War also made it impossible to travel to nearby Alsace or Markgräflerland, so the radius of action remained limited to Switzerland and the immediate vicinity of Basel.

My father once mentioned that their vacations and excursions were real educational trips. Hans Wittwer was keen to introduce his three sons to Switzerland and expand their knowledge of the country. The trips were always made by public transport and - a peculiarity that was repeatedly mentioned - did not lead directly to the destination, but always via various main and branch lines and therefore involved frequent changes. Everything always went smoothly and connections were made, as the entire journey had been meticulously planned with the help of a timetable. Their father gave them information about the individual train routes, and he also told them lots of interesting facts about the places or areas they passed or where they changed trains. Even destinations that were not very far away were only reached after a long journey. Once it was already dark when they finally arrived at their destination, some small house. They were all the more surprised when they opened the shutters the next morning and discovered that their seemingly unspectacular overnight accommodation was on the shore of a lake and the rising sun was shining directly into their room.

My father has vivid memories of their vacations in Lauenen. Three times, in 1943, 1947 and 1948, they spent a few days in the Maiensäss of a family who moved to their alp for the summer. The house had been arranged for them by an association that made it possible for families from the cities to spend their vacations in seasonally vacant houses of mountain farmers for little money. One of their three stays in the then still quite remote village in the Bernese Oberland was particularly memorable. The journey there was again made in several stages. The first was by express train from Basel to Bern, where they changed to a train to Fribourg (Freiburg im Üechtland). Here they toured the city and enjoyed a picnic prepared at home in a park. This was another of Hans Wittwer's peculiarities, which my father mentioned several times: his father avoided all restaurants. Meals were eaten either at home or outdoors, but never in a pub. The tour of Fribourg was followed by a trip to Bulle in the Postbus, which was undertaken especially to show the family the Saane valley with its characteristic meanders of the little river. In Bulle, they switched back to rail and boarded a narrow-gauge train, which took them via Château d'Oex to Gstaad.Here the group, who were now beginning to feel tired as they were also carrying quite a bit of luggage (the heavy suitcases had been transported by rail directly via Bern and Spiez), climbed back into a Postbus and finally reached their destination late in the afternoon, the idyllically situated village of Lauenen, where they spent their week's vacation in the Maiensäss.

My father has vivid memories of their vacations in Lauenen. Three times, in 1943, 1947 and 1948, they spent a few days in the Maiensäss of a family who moved to their alp for the summer. The house had been arranged for them by an association that made it possible for families from the cities to spend their vacations in seasonally vacant houses of mountain farmers for little money. One of their three stays in the then still quite remote village in the Bernese Oberland was particularly memorable. The journey there was again made in several stages. The first was by express train from Basel to Bern, where they changed to a train to Fribourg (Freiburg im Üechtland). Here they toured the city and enjoyed a picnic prepared at home in a park. This was another of Hans Wittwer's peculiarities that my father mentioned several times: his father avoided all restaurants. Meals were eaten either at home or outdoors, but never in a pub. The tour of Fribourg was followed by a trip to Bulle in the Postbus, which was undertaken especially to show the family the Saane valley with its characteristic meanders of the little river. In Bulle, they switched back to rail and boarded a narrow-gauge train, which took them via Château d'Oex to Gstaad. Here the group, who were now beginning to feel tired as they were also carrying quite a bit of luggage (the heavy suitcases had been transported by rail directly via Bern and Spiez), climbed back into a Postbus and finally reached their destination late in the afternoon, the idyllically situated village of Lauenen, where they spent their week's vacation in the Maiensäss.

Hans Wittwer had introduced a rhythm of "work" and "free days" for the vacations they spent together. On their work days, they did the shopping, worked around the house and read a little, while their excursions and hikes were undertaken on their "free" days. On their hikes, they mostly moved freely in the countryside and only rarely on (frequently used) paths. Hans Wittwer preferred to put together his own route with the help of maps, but liked to ask the locals whether the tour he had planned was feasible. However, he avoided getting straight to the subject of his actual interest. Instead, he began with a chat that initially revolved around very general things, about the weather or the harvest, asked farmers and herdsmen about their animals and only gradually steered the conversation towards the questions that interested him; how safe the terrain was, how long they would be on the way, whether there was still snow, etc. When planning a hike from Lauenen over the Sanetsch Pass to Sion, Hans Wittwer again made inquiries in his own systematic way. My father remembers them particularly well because one of the locals questioned was rather evasive when asked about the accessibility of the terrain, became visibly nervous and kept looking at the three sons, especially the youngest, who was only 8 years old at the time. The tour was not undertaken because the weather changed. On one of their later stays, they then undertook the hike on the last day, bringing their suitcases to the village beforehand to send them home by post and train, and finally set off with their rucksacks to Sion in Valais and drove back to Basel from there.

They did a lot of botanizing on their tours, albeit under the guidance of their mother rather than their father. Hans Wittwer mainly explained geography, geological formations and natural phenomena to them. For example, he once gave them detailed explanations when they witnessed a large piece of ice breaking off a glacier on a hike from Lauenen. He pointed to a rock that was next to the ice field near the breaking point and explained that the rock heats up in the sun and causes the ice to melt at this point until it is so thin that it breaks. He also mentioned that the process was called "calving" by glaciologists and took a picture with their camera.

Hans Wittwer also paid close attention to the interests and wishes of his three sons during the vacations. He helped his youngest to build a sailing boat based on the model of Nansen's Fram and carried the little ship up the mountain, where it made its maiden voyage in a small lake with its sails set. He thought of something else for his eldest. Following the example of mountaineers at the time, they set off to climb the Arpelistock in full darkness and made the first part of the ascent by the light of a lantern with a candle burning in it. As finding and illuminating the path required a great deal of concentration, they took it in turns to carry the lantern. When they arrived at the Arpelistock, Hans Wittwer unpacked a stove and made soup. They would probably have been able to find their way without artificial light and a cold picnic would also have strengthened them, but the lantern, stove and soup gave their tour, which was only undertaken by two people, a touch of adventure and romance, Hans Wittwer wanted to make his eldest happy. They were back home at the Maiensäss by 3 pm.

The place where they rested on their excursions and hikes was determined by the view it offered. When hunger began to set in or lunchtime approached, Hans Wittwer would simply stop and say, "We'll rest here. The whole family would then settle down, set up a stove powered by petrol or metatablets and prepare soup or tea. A hot meal or at least a warm drink was simply part of the deal. After the meal, Hans Wittwer unpacked his painting utensils, a sketchpad and a watercolor box, sketched the landscape with a few pencil strokes and painted a picture.